Thursday, September 18, 2014

Legacy ("Dr. Mütter's Marvels" by Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz)

When Thomas Mütter died in 1859 at the age of 47, friends and colleagues alike celebrated his life and career while also bemoaning the possibility that he might someday be forgotten. After all, his importance to medial science and the field of surgery was extraordinary. He was one of the first surgeons in the country to use early forms of anesthesia, which enabled him to perform complicated and often primitive procedures with little pain inflicted on his patients. He also embraced the idea that doctors should operate in sterile environments as to prevent infection and the spread of bacteria; that the care patients received after surgery was just as important as the care they received during surgery; and that doctors should treat their patients with compassion and understanding rather than indifference, as though they were little more than walking, breathing cadavers on which to experiment. All of these notions were newfangled and even controversial at the time, and Mütter faced pushback from many of his own colleagues, who felt as though any challenge to the status quo was an affront both professional and personal. Mütter belonged to a generation of surgeons who saw the limitations and mistakes of his chosen field and worked to change them for the better--to put the patient's wellbeing first and disregard ego completely.

In writing the story of Thomas Mütter from beginning to end, and even beyond those two seemingly final boundaries, Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz has fulfilled the wish of many of those who hoped for an "able hand" to someday write his biography--the story of "a great and good man," a pioneer in American medicine. And while it took more than 150 years for that book to be written--during which time American medicine advanced with such speed and breadth that even a man as forward-thinking as Mütter would be astonished--it arrived at a perfectly opportune time, as the legacy of Thomas Mütter has evolved over that same span of time into something he would have never expected. Today, this accomplished and altruistic man is known for the museum that bears his name and the thousands of specimens housed within its fireproof walls: evidence of medical mysteries, anatomical anomalies, and disquieting disfigurements. There is the death-cast of Chang and Eng, history's most famous Siamese twins; glass cases filled with skulls; organs, tumors, and growths preserved in jars; an 8-foot human colon; the body of a "soap woman"; the face of a horned Frenchwoman; and dozens of artistic renderings of those who suffered from horrifying deformities, among many others.

In truth, this museum seems almost tailor-made for our current age, where morbid curiosity can be veiled by the anonymity of the Internet, photographs and articles can be shared to millions at the touch of a finger, and various aggregator websites can use the museum's seemingly endless collections to increase their click-and-share statistics with attention-grabbing headlines. It's tempting now to see Mütter's museum--the encapsulation of his life's work, his philosophy as a doctor and man--as a Barnumesque sideshow, its tents and flaps replaced by beautiful architecture and an association with one of Philadelphia's great colleges. However, the gawk-and-share attitude of our modern age makes us unable--or maybe even unwilling--to see the truth behind Mütter's legacy. Rather than preserving these thousands of specimens because of their shocking nature, he did so because of the stories behind them. When Mütter operated on a patient suffering from strange or startling problems--a face deformed by burns, say--he looked them in the eyes, treated them like human beings rather than untouchables, talked them through the procedures, and looked after their comfort during the operation, which was especially important in the years before anesthesia. Where others, including Mütter's own colleagues, saw patients whose impairments made them less than human--and therefore less deserving of kindness or respect--he saw them as equals in need of his help. Mütter's legacy is one of empathy and grace, two traits that are downright necessary when treating people suffering from debilitating ailments, and his museum is a testament to his ability to look beyond the damage into the person beneath. To feature these scars in a museum is to create a monument to Mütter's humanity--a collection of pieces that speak to his ability to see beyond the pain they caused and recognize the frailties, and promises, in us all.

Sunday, September 7, 2014

Hypothetical ("What If?" by Randall Munroe)

Let us imagine for a moment an astronaut adrift in space. Never mind how he came to be in this predicament, or how he's been able to survive so long--for it has been a long time--floating without sustenance, water, or fresh oxygen. Never mind any of that. Instead, imagine that he finds himself drifting towards a black hole. As he approaches what would certainly be a sight of unprecedented beauty--a whole celestial body so dense it draws in everything around it at a gravitation speed unlike anything else in the universe--he begins to warp physically. Whatever body part is closest to the black hole--in this case, we'll say it's his feet--will be pulled by the star's immense gravity, even as the rest of his body remains outside of that same pull. This will cause his feet--bones, muscle, and skin--to stretch into unimaginable lengths. And because the black hole acts with such speed, there will not be time for his feet to detach from the rest of his body. Instead, this stretching will continue to affect one body part after another--ankles, lower legs, knees, thighs--until it reaches the pelvis, at which point the difference in gravity at the toes and head will be so great that the molecules of the body will no longer be able to hold this poor astronaut together, and he will separate.

The astronaut, needless to say, is not happy about this.

Unfortunately for him, he and his lower body are still drifting towards the black hole, and the gravity now begins to affect his upper half in the same way it affected the lower half. The pelvis and gut, the chest and hands and elbows, the arms, the shoulders, and finally the neck and head--all of it will be pulled down at different rates, stretched, and snapped into even more pieces, until the entirety of the astronaut is little more than a cloud of atoms being funneled down towards the mass' surface. Everything--bone, tendon, skin, organ--will become little more than microscopic traces of the man's existence, never to be found. After all, black holes are the unforgiving cemeteries of the universe: anything that approaches a black hole and crosses the event horizon, even light, can never escape, regardless of whether or not it had any choice in being there in the first place. Such is the case with our poor astronaut.

This entire process has a name: spaghettification. I learned about this when I was about twenty-five years old, from an interview with Neil DeGrasse Tyson that had been posted online. Had I learned about this ten years earlier, when I was still in high school, perhaps I would have actually enjoyed my secondary science classes. That is, had I been properly informed of all the inherent dangers of the world and universe around me--not just the spaghettifying effect of black holes but the "degloving" affects of an atomic blast, which I learned about from the History Channel, or the ant-zombifying fungi featured in online science articles--I would have sat with rapt attention, astonished at the universe's beautiful and violent indifference to us, and the increasingly bizarre ways in which it could snuff us out at any moment, should the situation permit it.

Or even when the situation was illogical, improbably, or even impossible. It wouldn't have mattered to me. I would have taken copious notes, disgusted my parents with the gruesome details over dinner, sought out and devoured books on the topic. And while I most likely wouldn't have understood anything beyond a few basic words among the technical jargon, it would have shown me the potential of science--the secrets it held, the possibilities it embraced--rather than boring me with rote equations, sophomoric vocabulary terms, and chromatic textbook diagrams. Where I should have suffered a Broadway-level range of emotions every day in class--joy, confusion, horror, anger, sadness--I instead was only bored. Where I should have been told to stand and move around, to poke and dissect and investigate, to stare at the unknown through microscopes or cast studious eyes up into the dark heavens, I was given one large tome after another and told to fill in the worksheets. Perhaps, if science had been presented to me in a different and much more descriptive way, I would have graduated with a greater respect for science and its many fields rather than a begrudging acknowledgement of its importance to accompany the B's and C's that littered my transcript.

In What If?, I finally find the book I'd needed then--and, possibly, the book most curious but easily bored high school students need still today. Compiled from his online webcomic, which features stick-figure representations of various hypothetical scenarios--a baseball pitched at 90% the speech of light, for example, or a quick swim around a nuclear fuel pool--Randall Munroe's book is based in deep research but avoids slipping into snore-inducting disquisitions. He is, in a way, the cool science teacher you always wish you'd had in middle school, except his lessons would most likely have gotten him fired. Take, for instance, the aforementioned fastball, pitched at 90% the speed of light--an act that, if possible, would decimate not only the pitcher and hitter but everyone in the stadium and much of the surrounding neighborhood, as the air in front of the baseball would be compressed with such speed that it would trigger rounds of fusion, blast gamma and x-rays, and wreak apocalyptic havoc, "all in the first microsecond."

Or take the jet-pack made of machine guns. Alone, an AK-47 is only powerful enough--when fired downward--to lift a squirrel into the air, though it would run out of ammunition long before that lightweight little rodent became the first representative of its species to be launched willingly into space. (Munroe never discusses whether this lone squirrel would actually be consenting to this ride, as squirrels don't consent to much of anything. Then again, its decision to remain on the gun seems like implied consent, unless of course some conniving scientist has glued its tiny feet to the gun. Such are the unanswered questions of science, I suppose.) An entire platform made of machine guns would also be ineffective, rendering any hopes of a newly resurrected space program--the National Aeronautics and Second Amendment Space Administration, or NASASA--moot.

What makes Munroe's work worthwhile is not just his understanding of science--he is a former NASA roboticist and graduated college with a degree in physics--or his ability to convey that information in a humorous and easy-to-understand way, but also the way in which he bases every witty explanation in scientific fact. In the process of reading about hypothetical situations, not all of which Munroe himself takes seriously, he is teaching his readers the most important and integral scientific concepts, many of which we've probably forgotten since high school...or never learned to begin with. This includes gravity, velocity, momentum, the Periodic Table, chemistry, and probability, many of which are complemented with diagrams and equations that are often complex but never complicated when put into context and explained. It's a textbook for the bored, attention-deficit, darkly humorous misfit in all of us--that middle-aged kid sitting in the back of his high school science class drawing silly pictures in his notebook, hoping against hope that maybe, just maybe, his teacher might explain to him just what a hypersonic hockey puck would do to the human body.

After all, a kid can hope, can't he?

Friday, September 5, 2014

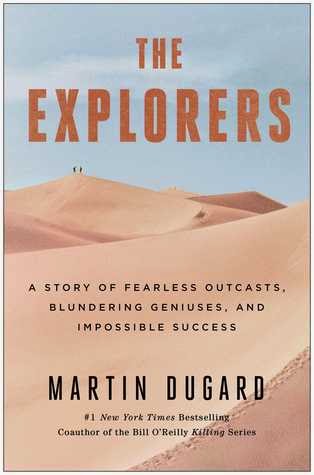

Perspective ("The Explorers" by Martin Dugard)

This past summer, in a fit of curiosity, I began writing a book about Christopher Columbus. To be honest, I had wanted to write a history of slavery in Wisconsin, my home state, but every attempted first chapter--on Jean Nicolet, the Jesuits, John Cabot--felt flimsy and incomplete, and only when I began to study the four voyages of Columbus, none of which ever touched the continental United States, did I find the opening story that I was missing. And while this idea seems strange--Columbus died more than 100 years before Jean Nicolet made his way into Green Bay and down the Fox River, and 300 years before Wisconsin actually became a state--his story perfectly foreshadows every major theme from that later history, from hapless expeditions and complicated relationships with indigenous populations to horrid greed and the origins of widespread indoctrination and indentured servitude. To write a book about slavery in America, regardless of what century or state, is to contend with the legacy of Columbus.

In the course of researching Columbus' life and expeditions, I had the chance to read two very different kinds of texts: firsthand accounts, including Columbus' own journals, and works of historical nonfiction from the last twenty years, which also used information from those journals but with much more finesse and context. Needless to say, the firsthand accounts were more helpful, even if it meant tirelessly attempting to separate factual events from manufactured self-promotion--Columbus was a master at the latter and terrible at the former--and looking desperately for other sources to fill in the missing pieces. That is where the recent books came into play, as they could be helpful--I hoped--in revealing paths to discovering what I had missed.

Instead, what I found in those books was nothing short of sacrilege. Based on little more than a desire to tell an interesting story rather than convey unblemished history, these modern-day writers wrote of Columbus as though he were a swashbuckling pirate or foolhardy kiss-ass. (That's not to say he wasn't both of these things at times, but rendering him as such through Indiana Jones-style prose is not the same as showing it through data.) Columbus, his crew, and the native people were ascribed with thoughts and emotions that were never recorded, only inferred, and the ecosystems of various islands were described in incredible detail, even down to the particular weather on a particular day and how it affected the trees and plans, even though those islands have not existed in those pristine, almost untouched states for centuries.

A perfect example of this habit can be found in Martin Dugard's retelling of Columbus' final voyage, which was fraught with disaster from the very beginning and never improved. Writing of Columbus' imprisonment at the end of his third voyage, Dugard writes that Columbus' ankles "had long ago been rubbed raw by iron shackles," and that "even lying flat on his back, he could feel their heaviness against his flesh and anticipate the manacles' noisy clank as he threw his feet over the bed." Dugard continues, "A verdant morning breeze wafted in through the window, on its way from the green mountains of Hispanola out to the Caribbean's turquoise waters. The fragile gust was yet another reminder that the freedom of wind and open sea--the freedom that had defined his life--beckoned less than half a mile away." All of these descriptions are contained in only the first two paragraphs of Dugard's entire book, and the remaining 250 pages are no better. If any of this information--the raw ankles, his anticipation of the shackle's clank, the fragile gust reminding him of freedom--is drawn from the firsthand literature of Christopher Columbus and his crew, it's gone unpublished.

Much of this is the fault of Dugard himself, who could have easily dispelled any accusation of over-fictionalized history with a thorough and detailed bibliography--a necessity when writing about important but controversial events and people. Many modern histories of Columbus do not contain a bibliography, and Dugard's writing is only supported by a "Notes" section and a seven-page "selected bibliography" that does not contain any specific attributions. (In many cases, Dugard lists only two or three books as the sources for his lengthy chapters, including Washington Irving's own fictionalized history of Columbus, which has been thoroughly invalidated by historians.) Had Dugard followed the examples of other, more notable historians and history writers, whose bibliographies often run over one hundred pages and cite every single quote, he might have realized the problem ahead of time.

Unfortunately, Dugard's most recent book--another history of exploration, this time focused on Richard Burton and John Speke--suffers from the same problems. At the end of The Explorers, where there should be a bibliography, Dugard offers us only a lengthy paragraph listing the titles of books he consulted; where there should be a detailed, fifty- or sixty-page list of pages and citations, there is an acknowledgement of all those whose writing influenced his own, as well as a justification for the extensive and distracting footnotes that litter every other page and add very little to the overall history. (In one instance, Dugard's footnote about explorer Sebastian Cabot becomes a discussion of the Family Affair actor of the same name; in others, he mentions the habit of South Floridians to dispose of their exotic pet snakes into the wild, offers a hypothesis on why the brain preserves some memories differently than others, explains the results of a Harvard study on daydreaming, and acknowledges all of the various places named after men like James Cook and Christopher Columbus.) Nowhere are we given direct evidence that much of the detailed, narrative-driven minutia included by Dugard actually happened or are certifiably accurate.

What's more, this is not Dugard's greatest transgression. Rather, the lack of adequate citations and his incessant need to footnote a legitimate historical topic with irrelevant bits of trivia pales next to an understanding of world history that is not only flawed but offensively blind. Much of Dugard's book is built on his inability to see beyond a Westernized version of history that values European explorers over indigenous people. Time and again, the white male Europeans in Dugard's book are "discovering" places that had already been occupied for centuries, if not millennia, while discounting those who were native to these regions. Even though these places were often the ancestral homes to millions, it took the arrival of Europeans to legitimize it, and it was those same men who were given credit. This level of Eurocentrism has dominated history books for generations, personified by Columbus' "discovery" of islands that were inhabited by people for thousands of years--an event that we celebrate every year, despite the fact that Columbus' arrival commenced the eventual exploitation and extermination of entire ethnic populations.

Perhaps the most egregious example of this mindset can be found in a tangential section on Howard Carter, who unearthed King Tut's tomb in Egypt under the supervision and funding of fellow Englishman Lord Carnovan. Keeping in mind the historical importance of this tomb to the region, not to mention its importance to the people of Egypt, Dugard's summary of this excavation is nothing short of clueless: "All because Carter and Carnarvon wouldn't quit. All those years of perseverance paid off. The results can be viewed in museums such as the exhibit within Highclere [Carnovan's estate] dedicated to the earl's collection of artifacts discovered during the years he indulged his passion for Egyptology." (Dugard 245) The terminology Dugard employs here shows a total disregard for what Carter and Carnovan did: they unearthed important artifacts, yes, but they did it to steal rather than preserve them or return them to the Egyptian people, since everything they found was part of that nation's history and culture. Instead, Dugard believes it's a testament to the tenacity of European explorers that these two men stole another culture's precious artifacts and either locked much of it away in stately manors for their own enjoyment or--presumably--sold it off for financial gain.

Dugard's book is organized to tell the story of men like Burton and Speke--men who put their own lives on the line to go places where they'd never dreamed of going before, all because those locations happened to be there.* But by embracing only one perspective--that of the invaders, the conquerors, the victors, the white European men--Dugard is implicitly elevating their story while disregarding the hundreds of years that preceded their arrival, yet another form of colonialism, exercised now over history itself. In fact, it was often the arrival of men like Burton and Speke that brought about the end of these native populations, and in horrible fashions: through enslavement, violence, bloodshed, rape, exploitation, and death. And yet they're seen as the ones worthy of praise, adulation, and study.

The great tragedy of Dugard's book, beyond what has already been mentioned, is that one of his chapters--"Independence"--is absolutely beautiful. In discussing the traits needed to be a world-class explorer, Dugard discusses the science behind introversion and extroversion, concluding that those most likely to walks thousands of miles without a second thought or crawl through a deadly African wilderness for years at a time are a special breed of person set apart from the rest of society. They are not fulfilled by interactions with others--in fact, just the opposite--and find solace in solitude, where they can think over pressing issues and push themselves to becoming better, more educated people. Had Dugard balanced his worship of explorers with a hardy and serious acknowledgment of their terrible legacies, he would have done justice to the very spirit of exploration without disregarding the souls of those it ultimately harmed.

*Female explorers are featured only twice: Isabel Godin, who walks across the Amazon to be reunited with her husband, and Amy Johnson, who earns notoriety for flying across half the globe and then dies in a plane crash within the span of only three pages

Monday, September 1, 2014

Self ("Eleven Years" by Jen Davis)

More than a decade ago, Jen Davis sat down in the sand of a South Carolina beach and took a photograph of herself. Featured in Eleven Years, this image shows Davis--overweight, pale, clad in a loose-fitting black tanktop and shorts--surrounded by two thin young women and a lean young man, all of whom are showing much more skin and seem almost unaware of her. She would continue taking photographs like these, in which she is alone in her own body--alone, even when in the company of others--until, years later, when she was suddenly among graduate students who did not know her, who looked at her photographs and talked abut her body in such a way that her body became unbearable. "I needed to make changes," she later said. "I didn't want to wake up at forty and be in the same body." She underwent laparoscopic surgery and, as some of the images in her collection demonstrate, lost much of that excess weight. Before then, however, she documented her life--her body--in photographs.

The harsh truth of these photographs, however, is that Davis' body is the reason for their popularity, for it is her body that elicits a reaction from viewers, demands analysis and commentary, and provokes controversy around the question of intent. Had Jen Davis been a slim, fit college junior when she took these photographs, they would have had little impact, as our society advances images like those on an almost continuous basis. There are clothing advertisements, billboards, magazine spreads, runway shows, and a near endless supply of movies and television programs that seem to portray a world populated by nothing but sultry, sexed-up young women with flawless skin and piercing confidence. As Anne Wilkes Tucker points out in the afterward to Davis' book, "Were it not for Jen's size, her pictures could easily be perceived as presenting a skilled and intimate life chronicle of a twentysomething girl. She hangs out with friends, eats at the local grill, washes clothes, and performs other daily activities."

While it may not have been her intent, Davis' photographs expose a harsh truth about the world in which we live: we stare at those who do not conform to our preconceived notions of beauty, and we do so with a mixture of fascination and disgust, as though they were below us simply because of their appearance. Even as obesity is proclaimed a dangerous epidemic, it's done so by the very same media that distorts our notions of beauty and forces us to evaluate one another (and ourselves) based on a ridiculous criteria, and we cannot help but cast long, unashamed glances at those who look like Davis, as though they had arrived from somewhere strange and alien to our own world--outsiders deserving of our scrutiny and criticism. But by taking photographs that focus exclusively on her weight, we the viewer are forced to confront this aspect of our collective selves, as Davis' photographs invite us to stare, if not outright demand it. This changes the dynamic of power in the relationship between those who stare and those who are stared at--between the viewer and the viewed--and in this way Davis can manipulate us through her photography and lead us away from our blind prejudice, if only slightly.

Photographs are, at their very heart, windows that transform all observers into voyeurs, as Wilkes Tucker notes. Every photograph is a peek into somewhere new and foreign, whether it be the sweeping ridges of a mountain range, a wide-angle portrait of a bustling city street, or the dimly-lit kitchen of a single young woman's apartment. And we are allowed to peer in without interruption and for as long as we want, all without the possibility of being discovered by those whom we watch. It is an invitation to gawk, and yet, when presented with photographs of Davis, we suddenly cannot. It is not disgust this time but shame--shame for ourselves, for knowing that we can indulge in the very same voyeuristic fascination that consumes us on sidewalks or in the aisles of a supermarket without fear of being sighted, but our conscience won't allow us to. Suddenly, confronted by one of these women--one of the objects of our self-righteous inspections--we are forced to also confront this "object's" humanity, her isolation, her sadness. Of all the photographs in her book, taken over eleven long years, not a single one depicts her smiling in any way, even when wrapped in the arms of another person. In seeing Davis for the who of her being rather than the what of her body, we exorcise the distance we have placed between her and us--the alienness that we bestowed upon her with an almost violent defensiveness--and in doing so we acknowledge what we have in common rather than what separates us.

In an interview a few years ago, Davis remarked that her work "is ultimately about our discomfort with our Self." Note the use of capitalization and spacing--not discomfort with "ourselves" but our being, the person we are, the ways we define and see our own body and mind. In being given approval to look at Davis in all forms--clothed, naked, alone, coupled, in light and in darkness--we are forced to understand that photographs like these could just as easily be taken of us. Because when we mock and stare, we do so in subconscious self-defense against the very mirrors we refuse to turn and look into, for fear of what we might see...for fear of how those reflections will not match the image we have of ourselves. By turning the camera on herself--for hours upon hours, for eleven years--Davis refused to ignore the mirrors any longer and confronted the difference between the fantasy of herself and the reality of who she was. "Was" in past tense because the reflection changed her. "Was" because the woman we see in these photographs is not Jen Davis anymore. "Was" because the image and the photograph have been reconciled into one slowly developing single truth. "Was" because the person we saw was never actually that person to begin with.

|

| Pressure Point (c) Jen Davis, 2002 |

|

| 4 A.M. (c) Jen Davis, 2003 |

|

| Steve and I. (c) Jen Davis, 2006 |

|

| Untitled No. 39. (c) Jen Davis, 2010 |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)